About Our Lake

Our Projects

AIS (Aquatic Invasive Species)

AIS are non-native aquatic plants and animals that have been introduced into Wisconsin’s waters and cause or have the potential to cause environmental, economic, or human health harm. Listed below is information on two AIS that have been found in Long Lake, Curly Leaf Pondweed and Yellow Flag Iris, and one which has invaded a nearby lake, Zebra Mussels. If you have any questions concerning the removal/disposal procedures for AIS, feel free to contact Lisa Burns, Washburn County Land & Water Conservation/Aquatic Invasive Species specialist. For more information about Wisconsin’s AIS, visit the WDNR Invasive Species Page.

CURLY LEAF PONDWEED

Curly-leaf pondweed (CLP) is a submersed aquatic plant native to Eurasia, Africa, and Australia. It was first verified in North America in the 1840s and quickly spread throughout the Northeast and Great Lakes regions into the early 1900s. Curly-leaf pondweed typically reproduces via turions (i.e., vegetative propagules), generally formed in late spring and early summer. The plant naturally dies back soon after turion formation, and the turions remain dormant in the sediment during the remainder of the summer and early fall. When water temperatures cool, the turions germinate (i.e., start growing). While a small number of turions may germinate in the fall (and survive under the ice during the winter), the majority of the turions will germinate the following spring. Curly-leaf proliferates once water temperatures reach 50⁰F (10⁰C).

CLP has been present in Long Lake for many years. It does not currently warrant active management, but the LLPA does monitor its growth. If conditions begin to interfere with navigation and recreation, the LLPA will consider available management strategies in collaboration with the WDNR.

For more information on CLP, visit the WDNR CLP page.

YELLOW Flag IRIS

Yellow flag iris is a showy perennial plant that can grow in a range of conditions from drier upland sites to wetlands to floating aquatic mats. A native plant of Eurasia, it can be an invasive garden escapee in Wisconsin’s natural environments. With its striking yellow flowers and aggressive growth, this non-native species can quickly outcompete native shoreline vegetation, forming dense mats that disrupt the lake’s natural ecosystem.

Yellow flag iris is a beautiful and attractive plant with its large yellow flowers and long, sword-like leaves. When not flowering, yellow flag iris could be easily confused with the native blue flag iris as well as other ornamental irises that are not invasive. The blue flag iris is usually smaller and does not tend to form as dense clumps or floating mats.

Previously, it was only present only in small clumps in Long Lake, mostly along the developed shoreline between the Narrows and Crows’ Nest. However, in the past several years, there has been a significant increase in its spread. The growth near the dam is concerning, as the seed pods are spreading into the Brill River. In 2024 a pilot treatment by EcoNorth was undertaken and more expanded treatment is scheduled for 2025. This treatment is paid for out of LLPA funds at no cost to the landowner.

Small clumps can be controlled by digging up the plant, but care must be taken to remove all rhizomes, as they can persist for more than ten years in soil. Be sure to dispose of them in the trash, not a composter, for even a dried rhizome can survive for over three months. Gloves should be worn while handling because the sap can cause skin irritation to sensitive persons. All parts of the plant are toxic, especially the rhizomes.

Click here to view the June, 2025 Yellow Flag Iris map.

For more information on Yellow Flag Iris, visit the WDNR Yellow Flag Iris page.

ZEBRA MUSSELS

Zebra mussels are an invasive species which has not been found in Long Lake, but it has been found in nearby lakes.

Zebra mussels are small mollusks native to the Caspian Sea, Black Sea, and the Sea of Azov. They were accidentally introduced into the Great Lakes in the mid-1980s, most likely as larvae (also known as veligers) in discharged ballast water of commercial cargo ships and soon spread throughout Wisconsin through recreational activities. Zebra mussels can hitchhike on boats and trailers, allowing them to travel long distances between waterbodies. They may also be attached to any unremoved plants or hiding in the mud. Adults can survive outside of water for several days in moist conditions. Zebra mussel veligers can also be carried to other waterbodies by currents or by residual water left in boating and fishing equipment (e.g., live wells, bilge pumps, engine cooling systems, bait buckets).

The best defense against them is to keep them out of the lake in the first place. That can be difficult because of how they spread. Since they are small, one or two attached to a boat hull or outboard lower unit may not be obvious. They can live out of water for several days, especially in cool weather. Even more significantly, their free-floating larva start out as being microscopic, undetectable by the human eye. That is why it is so important to follow the rules about not transporting water from lake to lake. Visual inspection alone is not enough. Drain everything.

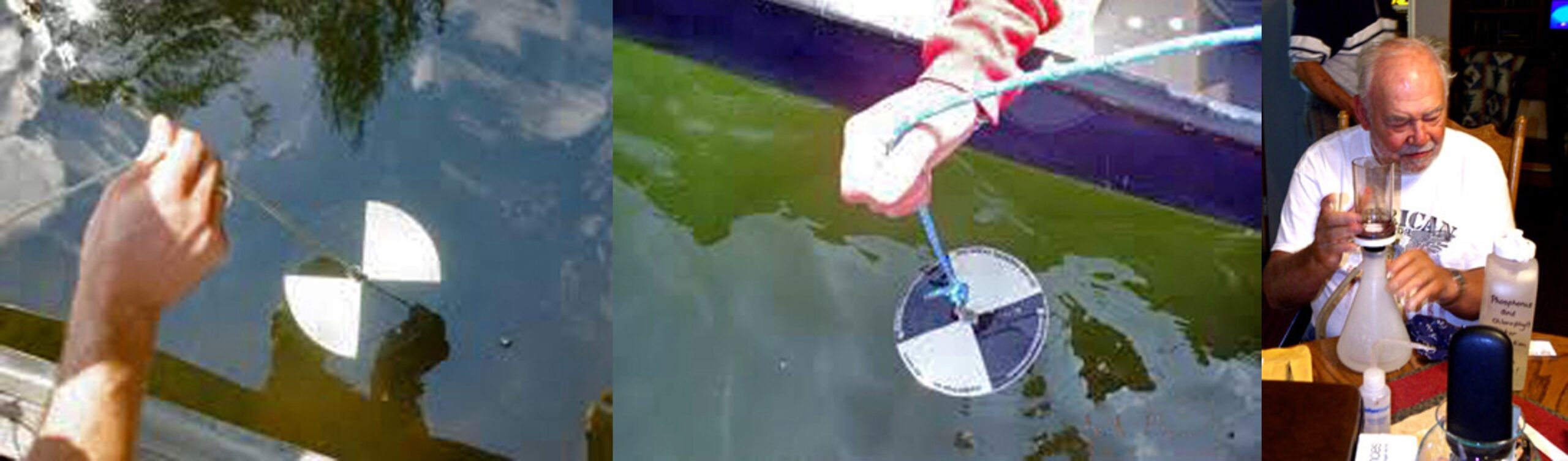

LLPA has continued Clean Boats Clean Water inspections at major landings. Additionally, because early detection gives at least some hope of control we have built Plexiglas devices known as collector plates and suspended them from docks at landings, the idea being that if they are present they will attach. Thus far all inspections have been negative, but only continual vigilance and adherence to the no water transport rules by every boater can keep them at bay.

For more information about Zebra Mussels, visit the WDNR Zebra Mussel page.

Water Testing

Fish Sticks

Trees have been dropping naturally into Wisconsin lakes since the glaciers receded. Fallen trees provide shelter and feeding areas for a diversity of fish species and may also provide nesting and sunning areas for birds, turtles and other animals above the water. Nearly all fish species use woody habitats for at least a portion of their life cycle.

The statewide Healthy Lakes initiative funds simple best practices like fish sticks, native plantings, and rain gardens on lakeshore properties. Fish Sticks are naturally inspired habitat structures—anchored trees or clusters of logs—added to the shallow near‑shore zones of lakes. They recreate critical woody habitat offering shelter, feeding, spawning, and basking opportunities for fish, birds, turtles, and more. Fish Sticks can also help prevent shoreline erosion – protecting lakeshore properties and the lake. Learn more about fish sticks at the Healthy Lakes and Rivers website.

The LLPA has installed 12 Fish Sticks projects as of 2025. Click here to view the most recent map.

Clean Boats, Clean Waters

The Clean Boats, Clean Waters (CBCW) program, coordinated by the Wisconsin DNR and partners like UW‑Extension Lakes and Clean Lakes Alliance, is a statewide initiative to reduce the spread of aquatic invasive species (AIS) in our lakes. You may have noticed Clean Boats, Clean Waters boat inspectors checking boats at the Long Lake boat landings. Clean Boats, Clean Waters includes teams of volunteers, who help perform boat and trailer checks, hand out informational brochures and educate boaters on how to prevent the spread of aquatic invasive species.

For more information on CBCW, visit the WDNR CBCW page.

Decontamination Station

The LLPA and the Long Lake Chamber of Commerce have jointly erected decontamination stations at the four major public landings.

Decontamination FAQ Sheet

Each station consists of a 4×8’ sign with a cleaning brush, weed removal hook, goggles and a one gallon sprayer containing a mild bleach solution. The bleach solution is targeted at larva of Zebra Mussels. Two of the stations were supplied by the Washburn County Land and Water Conservation Department, aided by a WDNR grant, and two were purchased by LLPA and the Chamber.

The bleach solution is for spraying all portions of boat, motor and trailer exposed to water. It should be noted that an ordinance enacted by Washburn County in 2018 states that if a decontamination station is available at a landing, it shall be used in accordance with the posted instructions. We all appreciate that this adds a little time unloading and loading, but if that helps keep invasives, especially Zebra Mussels, out of Long Lake, it is worth the effort many times over.

Rain Gardens & Maintenance

Hunt Hill is the permanent site of a green and growing collaboration between LLPA, the Audubon Sanctuary and UW-Extension. With the help of Master Gardeners, and others who attended the free how-to sessions, three impervious surfaces there now drain into rain gardens. The practice of planting native perennials in swales dug out to collect and cleanse storm water and snowmelt is climbing the charts of lake stewardship. In Seattle, Madison and suburban Twin Cites, entire neighborhoods and even some commercial sites have incorporated rain gardens. As an individual effort, anyone with shovel, wheelbarrow and trowel can make a significant difference in preventing fine sediment and pollutants associated with development from entering storm sewers, streams and lakes.

How to build a rain garden – manual

The rain gardens planted at Hunt Hill were designed to trap and filter runoff from the office, barn and a dorm. Each demo plot took into account slope, soil type, sunlight and surface area it would drain—in each case a roof. Downspouts direct storm water to the gardens, where it percolates through the soil and recharges the groundwater instead of racing across the lawn to the lake. Native plants were selected because they require minimal maintenance, no fertilizer and no pesticides. Each garden was mulched to retain moisture and choke out weeds, and down slope berms were seeded for easy mowing. Hunt Hill’s longtime conservation ethic means its slopes are not heavily contaminated by construction debris; automotive fluid leaks; household chemical, paint and wood preservative spills; and bacteria-laden pet waste. Or sedimentation from bare dirt piles, which kills off littoral zone fish and amphibian egg clusters. Or phosphorus from excess fertilizer, which grows whopper algae blooms.

But what’s happening at our homes? Even car-washing suds that pour off pavement and accumulate on lawns carry chemicals harmful to aquatic life. Since no one seeks out lakefront property only to have a dead zone offshore, it behooves each of us to practice lake-friendly living. Rain gardens contain storm water for only a short time, avoiding mosquito breeding. While doing so they create beauty and intensify life. Wouldn’t we all enjoy more blooms and butterflies, dragonflies and ground-nesting songbirds along our shores? The EPA calls polluted runoff “the nation’s greatest threat to clean water.”

Boat Landing Kiosks

The LLPA kiosk project was undertaken in conjunction with the Department of Natural Resources. Seven kiosks were built and placed at various watershed landings, including five on Long Lake. The additional kiosks are at Slim Creek Landing and on Little Devil’s Lake.

The structures are designed with a large display area for posters and information pertaining to DNR rules and regulations. Below is an area designated for informative pamphlets and cards identifying various exotic species. This LLPA project will provide updated and timely information for watershed visitors and riparian owners through the years, as people take advantage of the literature displayed.

Partners

Tomahawk Scout Reservation, operated by the BSA Northern Star Council of Minnesota, is located in the center of the “fish hook” on Long Lake. Encompassing 3,000 acres and 12 miles of shoreline, Tomahawk is home to the council’s summer Boy Scout and Webelos resident camps as well as the Snow Base Winter Camp. The Camp hosts LLPA’s annual meetings, and its Director is an ex officio (automatic) member of the LLPA Board of Directors.

A collaborative agreement between LLPA and Hunt Hill Nature Center involves Hunt Hill as our partner in watershed education, hosting our Cakes at the Lake programs and serving as the site of most Board of Directors’ meetings. LLPA also rents storage space there.

- Hunt Hill – hunthill.org

- Long Lake Chamber – longlakewisconsin.org

- Red Cedar Lakes Association – redcedarlakes.com

- Slim Lake Association

- Tomahawk Scout Camp – camptomahawk.org

- Walleyes for Tomorrow – walleyesfortomorrow.org

- Washburn Cty Extension – washburn.uwex.edu

- Washburn County Land & Water Conservation Department – co.washburn.wi.us

- WCLRA / Washburn County Lakes and Rivers – wclra.org

- WI DNR – dnr.wi.gov

- Wisconsin Assoc. of Lakes – wisconsinlakes.org

Current Lake Conditions

Water Clarity

LLPA water testing includes testing water clarity with a Secchi disk several times per summer. The five primary sites are as indicated on the accompanying map.

Water clarity results (measured in feet) for the recent years are shown in the following tables:

| Location | North End | Kunz Island | South End | Thumb | North Narrows |

| Date | A | C | D | E | F |

| May 2025 | 6.5 | 8.5 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 8.0 |

| May 2024 | 7.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 10.5 | 7.5 |

| May 2023 | 10.0 | 9.5 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 9.5 |

| May 2022 | 8.5 | 8.0 | 8.5 | 8.0 | 6.5 |

| May 2021 | Missing Data | Missing Data | Missing Data | Missing Data | Missing Data |

| Date | A | C | D | E | F |

| June 2025 | 10.0 | 9.5 | 9.0 | 11.0 | 10.5 |

| June 2024 | 8.0 | 8.5 | 9.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 |

| June 2023 | 13.5 | 14.5 | 13.0 | 13.5 | 13.0 |

| June 2022 | 8.0 | 9.5 | 10.0 | 9.5 | 8.5 |

| June 2021 | 9.5 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 13.0 | 11.0 |

| Date | A | C | D | E | F |

| July 2025 | 6.5 | 9.0 | 8.5 | 10.0 | 10.5 |

| July 2024 | 7.5 | 11.5 | 12 | 12.5 | 8.5 |

| July 2023 | 10.5 | 12.5 | 14.0 | 14.0 | 11.5 |

| July 2022 | 6.5 | 9.5 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 7.5 |

| July 2021 | 6.0 | 10.0 | 10.5 | 11.0 | 7.0 |

| Date | A | C | D | E | F |

| August 2025 | 4.5 | 6.0 | 8.5 | 7.0 | 6.0 |

| August 2024 | 5.5 | 9 | 10 | 10.5 | 5.5 |

| August 2023 | 7.5 | 10.0 | 11.0 | 13.0 | 9.0 |

| August 2022 | 10.5 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 8.5 | 9.5 |

| August 2021 | 6.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | Missing Data | 8.0 |

Wildlife Inhabitants

Bears

Photo Courtesy of Barb Ray

Living With Bears in Wisconsin

Black bears are commonly found in the northern third of Wisconsin, but are being sighted more frequently in the central and southern counties of Wisconsin as they expand their range. As the black bear population continues to grow, so do an increasing number of bear-human conflicts. In order for bears to coexist with humans, we have to understand normal bear behavior. Black bears tend to be shy, solitary animals, but at some times of the year, particularly in the spring when bears emerge from their winter dens and food is not abundant, bears may be on the lookout for opportunistic food sources. This might be your garbage can, or the bird feeder in your back yard. Nearly all human-bear conflicts are a result of the animals’ search for food. There are lots of simple things you can do to avoid conflicts with bears. With your help we can continue to live together with this great animal, enjoying their presence in the woods around us and at the same time reducing conflicts with bears around our homes and our campsites.

REDUCING BEAR CONFLICTS NEAR YOUR HOME

Black bears are attracted to numerous items around homes, including: bird feeders, compost piles, grills, pet food, gardens, and garbage. Here are some simple recommendations to avoid problem bears:

Bird Feeders

- Make bird feeders inaccessible to bears by hanging them at least 10 feet off the ground, and 5 feet away from tree trunks, or on a limb that will not support a bear (you can still refill the feeder easily by using a pulley system).

- Consider taking bird feeders down at the end of winter (mid-April) when bears emerge from their winter dens.

- During spring and summer, bring feeders inside at night, a time when bears frequent stations.

- Clean up spilled bird seed below feeder stations.

- If you see a bear at a bird feeder during the day, take the feeder down and discontinue all feeding for at least two weeks.

Garbage Cans

- Keep your garbage cans tightly closed, and indoors if possible.

- Pick up loose or spilled garbage so that it doesn’t attract bears.

- Occasionally clean out your garbage cans with ammonia to make them less attractive to bears.

And a few more…

- NEVER FEED A BEAR! Intentional feeding will create a bear that is habituated to humans, and may become a possible nuisance to you and other people in the area. The bear will not forget the feeding experience, and will tend to get more demanding with time.

- Bring in pet food at night.

- Clean up and put away outdoor grills after you are done using them for the day.

WHEN YOU ARE CAMPING

- Don’t cook, eat, or store food in your tent! The smell of food may attract bears.

- Store food and cooking utensils away from your campsite, preferably in a vehicle or hung in a tree at least 10 feet off the ground and 5 feet out on a limb that will not support a bear.

- Dispose of scraps in closed containers away from your campsite, not in the fire.

- Keep your campsite clean.

IF A BEAR IS CAUSING A NUISANCE IN YOUR AREA

Contact the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture Wildlife Services. In the northern half of Wisconsin, call 1-800-228-1368, or in the southern half of Wisconsin call 1-800-433-0663. They can help you by providing additional information on reducing or eliminating your specific problem. If the situation is severe and presents a threat to health and human safety they can also remove the bear from the area.

BLACK BEARS AND AGRICULTURAL DAMAGE

With a healthy black bear population, it is inevitable that black bears may damage agricultural crops in some areas. Particularly tasty treats are apiaries (beehives) and corn fields in the milk stage. Bears also occasionally attack livestock. The Wildlife Damage Abatement & Claims Program (WDACP) is available to help Wisconsin farmers whose crops or livestock are damaged by bears. If you would like more information on this program, please contact the Wildlife Damage Specialist at (608) 266-8204 or write us at

WI DNR, 101 S. Webster St. (WM/6)

P.O. Box 7921,

Madison, WI 53707-7921.

Facts about Wisconsin’s Black Bear

Weight: Males, 250-300 lbs; females, 120-280 lbs.

Body Characteristics: Bears appear bulky and are glossy black, with a tan patch across the nose. Brown and cinnamon colored bears appear less often.

Reproduction: Black bears are sexually mature at 3 years of age. Females will breed every other year from then on. Mating takes place from June to early July. During the 225-day gestation period, the fertilized egg experiences delayed implantation until late November or early December. Females then give birth to two to three cubs in January or early February while they are still in their winter sleep!

Cubs: At birth, the bear cubs weigh 7-12 oz. Their eyes are closed and fur is sparse. Growth takes place quickly. Cubs will first venture into the world with their mother in late March. They remain with their mother through the summer and usually den with her the following winter. In the springtime, the mother will chase off the cubs so she can breed again.

Diet: Bears are omnivorous, meaning they will eat almost anything! Their diet generally consists of vegetation, insects, berries, and nuts. Occasionally they eat carrion and small animals. They also target livestock, beehives, garbage, and agricultural crops.

Habitat: Large forested areas with swamps and stream bottoms, and areas with minimal development are good habitat for black bears They are also found around thick ground vegetation with lots of trees and bushes that produce nuts and berries. Fallen trees provide bears with locations to dig a winter den.

Behavior: Bears are typically shy and secretive animals; most go to great lengths to avoid humans. Bears typically wander over long distances. Home ranges are about 27 square miles for males, and about 8 square miles for females. Black bears are most active around dusk, but may be out and about any time of the day or night. Mid-May to late September is the period of most activity.

Winter Sleep: Bears are not true hibernators! During the winter months bears “den up” where they will fall into a deep sleep. During this time bears live off the body fat they have accumulated during the fall. Their body temperature, heartbeat, and respiration decrease, but not to the level where hibernation occurs. Dormant bears can be easily awakened from their winter sleep!

IF YOU SEE A BLACK BEAR

- Make noise and wave your arms—let the bear know you are there so you don’t surprise it. Bears normally leave an area once they know a human is around.

- If you happen to surprise a bear at close range, back away slowly.

- If you are near a vehicle or building, go inside until the bear wanders away.

- Do not approach a bear. Respect black bears as wild animals and enjoy them safely—from a distance.

WEBSITES WITH ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Information Courtesy of Wisconsin DNR Wildlife Education

Loons

Listen. That eerie sound you hear is not a ghost haunting a northern lake. It’s the call of the common loon. This bird, whose ancestors roamed the earth 65 million years ago, can be found on Wisconsin’s northern lakes in the summer. They come here to breed and raise their young. Come fall, they head to the ocean coasts to overwinter. (You can track migrating loons as part of a loon migration study.)

What’s for dinner?

Common items on the loon’s menu are perch, bullhead, and sunfish. They’re also known to eat frogs, crayfish, and even leeches—yum,yum. Check out the loon’s long, pointed beak—the better to grab fish and other goodies. The loon dives underwater to grab its prey and then swallows it in one gulp.

Living on the water

Loons are made for living on the water. The torpedo-like body is streamlined for swimming underwater. The legs of a loon are set far back on its body to work like oars with its large webbed feet. The body color, dark on top and light on the bottom makes loons less visible to fish as they swim. Some scientists think the loon’s red eyes help it see better underwater.

Because the loon’s legs are so far back on its body and because its body is so long, loons have trouble taking-off. Have you ever seen a loon “running” across a lake? A loon has to run across the water for up to ¼ mile beating its wings in order to get enough lift to take off. This need for a long runway means that loons need a certain size lake in order to take off. You’ll rarely find a loon in lakes under 9 or 10 acres.

The loon dance

When disturbed the loon folds its wings against its body and swims upright in what is called a penguin dance. With its wings tucked against its body it looks kind of like a penguin. This dance is done when the loon is trying to scare enemies away from its chicks. “Dancing” like this takes a lot of energy so it’s important that you keep your distance from loons. If you get too close to it and its chicks or nest, the loon will think you’re its enemy and start the penguin dance. If you don’t leave the area, the loon can dance until it’s exhausted and dies.

The loon has another dance that it does when it wants to chase away other birds. It splashes the water with its wings and kicks its feet so quickly that it is actually walking on water.

Loon nests and hitchhikers

Loons are fast in the water but have trouble walking on land. They don’t spend much time on land, except to nest. Their nests are made of weeds and grass and are usually located in grass along the lake shoreline. A loon may use the same nest year after year. Two olive-brown eggs are laid. Crows, ravens, gulls, skunks, mink and raccoons (especially raccoons) eat the eggs. Both male and female loons take turns sitting on the eggs. The eggs hatch in about one month. Soon after the eggs hatch, the chicks are in the water swimming with their parents. Swimming in the cold water is hard on the chicks, so from time to time they hitch a ride on their parent’s back. This also protects them from predators like snapping turtles and muskies.

Loon Watch

In 1978, the Sigurd Olson Environmental Institute in Ashland, Wisconsin started a loon conservation program. In 1988 it was combined with a program in Minnesota and given the name LoonWatch. This program trains volunteers to help protect loons and their habitats; track loon populations; and educate people about loons. It also sponsors research and education about loons. In July hundreds of Loon Watch volunteers will get up before the sun to go count loons on more than 250 lakes. The results of this survey will help biologists track the number of loons in Wisconsin.

Loon Watch, its Advisory Council, and volunteers are all working toward common goals of loon conservation and protection. For more information about the program, contact the Sigurd Olson Environmental Institute at Northland College, (715) 682-1220, or email loonwatch@northland.edu.

Loon lore

There are many Native American stories about loons. The Ojibwa (Chippewa) Indians called the loon “Mang” or “the most handsome of birds.” They thought the loons’ haunting cry was an omen of death. In some native legends the loon is a bird of magical powers, in others a messenger or a symbol of power. You can read some of these Native American stories in “Loon Book” by Tom Hollatz. Your public library should have a copy.

If you get a chance to visit Long Lake this summer, listen for the haunting call of the common loon.

Loon Resource Links and Audio/Video Files

Wisconsin loons have been dying from botulism toxicity while migrating through the Great Lakes in the fall, including our banded adults and juveniles. Attached you will find a YouTube video that describes the issue very nicely.

Check out Kevin Kenow’s USGS website to learn what work is ongoing here in Wisconsin to understand the link between invasive species and loon mortality.

Loon Calls

Loon calls at night. Experience the sounds of the Northwoods

Long Lake Loon Ranger

Byron Crouse, (715) 635-6518

Please call or email Byron to report a loon on a nest or a loon in danger/distress

Beavers

The Beaver is North America’s most common and largest rodent. Their most distinctive feature is their large flat tail, which serves as a rudder when swimming, a prop when sitting or standing upright, and it is a storehouse of fat for the winter. They are an aquatic mammal with large webbed hind feet ideal for swimming and hand-like front paws that allow them to manipulate objects easily. They have excellent senses of hearing and smell. When swimming under water a protective transparent membrane will cover their eyes and a flap closes to keep water out of their nostrils. They also have inner lips to keep water out when carrying sticks in their mouth. Beaver fur consists of short fine hair for warmth and longer hair for waterproofing.

Beavers are pure vegetarians, subsisting solely on woody and aquatic vegetation. They will eat fresh leaves, twigs, stems, and bark; preferring aspen, birch, cottonwood, maple, poplar and willow. Aquatic foodstuffs include cattails, water lilies, sedges and rushes.

Beavers build and maintain houses called lodges. The most recognized type is the dome shaped dwelling surrounded by water. It is made of sticks, mud and rock. Each lodge has a minimum of two chambers: one for sleeping, one for eating and grooming. They have at least two water filled tunnels leading from a chamber to the pond so the beaver can enter and exit the lodge underwater without being spotted by predators. Their babies, called kits, are born and nursed each spring. Beavers weigh 45 to 60 pounds. They mate at three years of age and they mate for life.

Beaver don’t hibernate, so they stock pile sticks under water. When the ponds freeze they remain in the lodge and leave only to retrieve sticks from the stock pile to eat.

The beaver’s ability to change the landscape is second only to humans. Thus the beaver has developed a bad reputation among some because they can cause roads to flood with their damming capabilities. But wetlands behind their dams lessen erosion, and act as a water purifier; creating a watery habitat for fish, turtles, frogs, birds and ducks. So the beaver’s ability to maintain the health of this ecosystem cannot be understated.

Chickadees

Poecile atricapillus, the Black-capped Chickadee, is a common neighbor at Long Lake. Although largely out of sight and relatively silent in summer, these birds are non-migratory, and with the fall of autumn leaves come flocking, the occasional “fee-bee” call of summer giving way to the familiar “Chicka-dee-dee-dee.”

If we listen carefully we can detect multiple calls, and the birds do use them for communication. The familiar Chicka-dee-dee can be an alarm call, with the number of “de’s” corresponding to the threat level. Other birds which tend to associate with Chickadee flocks do respond to their alarm calls, even when that species has no similar alarm call of its own. Other interesting facts concerning this tiny bird, according to the Cornell University Ornithology Lab, include:

- When you see them take one seed at a time and fly off with it, it may be to eat it, or it may be to hide it. Each morsel is placed in a different spot, and the bird can remember literally thousands of hiding places. To accommodate that kind of memory, every autumn brain neurons die and are replaced with new ones.

- The birds form flocks in the fall, and each flock has a social hierarchy. Some birds, known as “winter floaters,” associate with multiple flocks, and may have a different social rank in different flocks.

- Although they form flocks in winter and find mates for the following year then, each bird sleeps alone. Even in sub-zero temperatures they find a hole in trees, which they can easily excavate in dead wood.

- The oldest known Chickadee was re-captured in Minnesota 11 ½ years after it was originally banded.

Black oil sunflower seed is a favorite food, and they also enjoy suet. Cleanup of sunflower seed shells in the spring is a small price to pay for the joy of having them near the window all winter.

Snapping Turtles

Of the 21 species of reptiles in Wisconsin, 11 are turtles. Here we will focus on the largest and heaviest, the common snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentine.

Like all turtles, the snapper is cold blooded, obtaining heat from the sun. Unlike the familiar painted turtle, snappers seldom crawl onto logs to sun themselves, but often float at the surface. They are almost entirely aquatic, with females coming to shore to lay eggs primarily in May and June. They will travel some distance to find a suitable egg laying site, having been found as far as a mile from water. Fortunately, the attempted housebreaking depicted in the side photo is not common behavior.

On land, snapping turtles can be quite aggressive. They should be handled only by those who truly know how. Lifting by the sides of the upper shell is dangerous, as they have a very long and mobile neck-the species name serpentine means “snake-like.” Their bite can easily sever a finger. Lifting by the tail could cause them permanent spinal damage. It is best to just watch them from a distance. In the water they are not a threat to humans, and when encountered they will swim away or hide in the muck or under vegetation.

Adult turtles have few predators, but the eggs are another matter. Nests are frequently raided by raccoon and skunks. Eggs that survive hatch in 80 to 90 days, although some overwinter in the nest. When a tiny turtle is seen heading for water in the spring, if is from an egg laid the prior year.

Snapping turtles are omnivorous, eating plants and just about any animal or fish they can catch, although their reputation as a duckling predator has been highly exaggerated. Younger turtles will forage for food, but the big ones hang motionless in the water, hunting by ambush.

River Otters

One of the most fun-loving furry critters in Long Lake is the River Otter, sometimes fondly referred to as a ‘Stick Tail.’ We lake residents are very fortunate to have this mammal as one of our entertaining neighbors as otters are mainly located only in the northern portion of Wisconsin.

Not to be confused with the muskrat, who swims in a straight line displaying definite purpose, otters are very playful. According to the Wisconsin DNR they like to wrestle, chase other otters, and play capture and release with live prey. In winter they will take three or four bounding steps and then slide across the snow for 5-15 feet.

The otter’s diet is an aquatic mixture of fish, birds, and vegetation. After diving for food they resurface, float on their backs and use their tummy as a dining table. You will see them just laying there munching away on their delectable harvest.

For homes, otters use abandoned beaver lodges, hollowed out logs, or brush piles. The mama otter will give birth to two to four pups in April or May after a one year pregnancy. Babies are born about 4.5 inches long, furry, with their eyes closed for about a month. In eight to ten weeks, they are ready to hit the water. After turning one year of age, otters leave the family in search of a territory to call their own. Due to their voracious eating habits, an otter needs to claim a territory as large as three square miles.

Interesting Facts

Measurements: length: 2-4 feet; weight: 44-82 pounds; tail length: 1-1.5 feet

Life Expectancy: 10-15 years

Extra Tidbits: largest member of the weasel family; makes high-pitched scream when fighting or mating and will snort when confused or surprised; can dive to depths of more than 40 feet!

Wild Turkeys

While once present in Wisconsin, wild turkeys completely disappeared due to loss of habitat during the lumbering era of the Nineteenth Century, the last known bird having been harvested in 1881. In 1976 Wisconsin traded ruffed grouse to Missouri in exchange for turkeys, releasing 29 birds in January of that year, with 334 more to follow. The reintroduction success has been phenomenal, with more than 45,000 birds being registered in the Spring 2016 hunting season alone.

The wild turkey is Wisconsin’s largest game bird, measuring 2.5 to 3 feet in height, with the male (gobbler) weighing in at 17 to 21 pounds and the hen at 8 to 11 pounds. Wingspans range from about 3 to 4.5 feet. Each bird has 5,000 to 6,000 feathers, which provide wintertime warmth, assistance in flight and which are sported in mating rituals.

Turkeys stay in flocks of 5 to 50 birds. The flock utilizes a home range of more than 1,000 acres. They prefer open grassy or grain field areas next to hardwood forests. The forest provides refuge from predators and a roosting place at night. Food consists of plants, insects, acorns, seeds and fruit.

Turkeys are wary, shy birds with excellent eyesight. They see in color, and have a 270 degree field of vision. They are capable of flying at over 55 miles per hour, but only for short distances. They prefer to run from predators, having a top speed of about 25 miles per hour.

While turkeys are North American birds, they originally derived their name, somewhat indirectly, from the nation of Turkey. They bear some resemblance to the guinea fowl of central Europe, sometimes called “turkey fowl” because originally imported there from Turkey. They are different birds, but somehow the name just stuck.

Had Benjamin Franklin had his way the turkey, not the bald eagle, would be our National Bird. Ben lost that argument.

Mudpuppies

A Mudpuppy (common to Long Lake) is a large, aquatic salamander with a flat, square head, small eyes and distinctive a pair of feathery gills on either side of its head. The Mudpuppy name is thought to derive from either the external gills which are reminiscent of canine ears, or from the erroneous belief that they make vocalizations similar to those of a dog.

The smooth skin of the adult common mudpuppy can differ in coloration between red, black and grey-brown, with variable scattered blue-black spots across its back or occasionally faint stripes. The underside of the body is greyish and may also have dark spots. The juveniles have a highly distinctive pattern, with broad, dark stripes with yellow edges along the back.

The tail is short and flattened and the legs are short and slender, but well developed, with four toes on each foot. The size of an adult Mudpuppy is 8”-12” (20-30 cm) long.

Mating between the common mudpuppy occurs between autumn and winter and the female lays between 40 to 150 eggs. The female guards the eggs until they hatch.

The common mudpuppy relies mostly on its sense of smell to detect prey composed mainly of aquatic salamanders or small fish and their eggs.

The common mudpuppy is active all year, although it is most active from late autumn to spring. It is primarily nocturnal, but may sometimes emerge during the day in habitats where the water is cloudy.

An entirely aquatic species, the common mudpuppy inhabits freshwater ponds, lakes, streams, canals, reservoirs and rivers. It lives close to the bottom where there are rocks and logs for shelter. The range of the common mudpuppy extends south from eastern Canada to northern Georgia in the USA.

The common mudpuppy is sometimes caught by fishermen then discarded onto land due to the false belief that it is poisonous or detrimental to the game fish population, which it is not.